Mobula rays are under threat. Unlike similar species such as manta rays and whale sharks, Indonesia’s mobula ray fisheries are unregulated. Amongst Indonesia’s widespread small-scale fisheries, mobula bycatch is likely to be a more significant threat than target fisheries. This makes designing and implementing regulations difficult. But there is hope, and through education and appropriate technologies, fishers can play an important role in protecting threatened mobula populations.

Indonesia has five mobula ray species

The five most abundant mobulid species reported in Indonesia are Mobula japanica (50%), Mobula tarapacana (24%), Manta birostris (14%), Mobula thurstoni (9%), and Mobula kuhlii (2%).

Our findings in Muncar support this, with M. japonica the most commonly landed species, followed by M. tarapacana and M. thrustonii. We have recorded landed individuals ranging in size from 30 cm to more than 250 cm disc width. We have even recorded pregnant females being landed.

Mobula rays in Muncar fishing port

Mobula rays have low reproductive rates

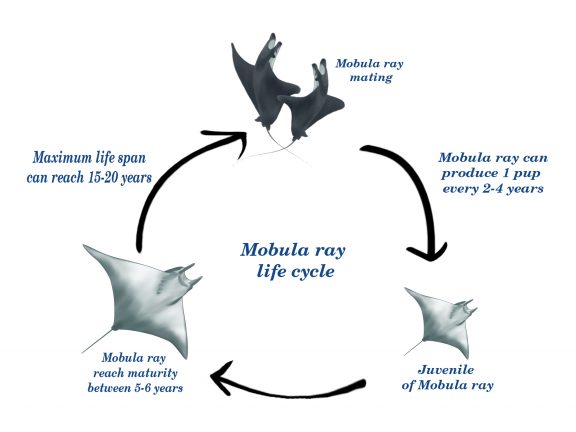

Compared to other Chondrichthyan species, mobula rays have lower reproductive rates and hence a higher risk of extinction.

Mobulas have a lower reproductive than other shallow-water species such as whale sharks and basking sharks. Female mobulid rays only have one active ovary and uterus and are able to produce only a single pup at a time. In contrast, a whale shark may have a litter of up to 300 pups.

Mobulas probably have a slightly higher reproductive rate than manta rays. Recent research by Pardo et al. (2016) indicates that larger mobulid species have lower somatic growth rates, lower annual reproductive outputs, and lower maximum population growth rates.

Similar to manta rays, mobulas may have a biennial cycle of reproduction, with one pup produced every two to four years. The life expectancy of a mobula is estimated to be between 15 and 20 years. By calculating the gestation period, inter-pregnancy interval, litter size, and assuming that Mobula japanica reaches maturity at around 5-6 years, this would suggest that a female mobula will produce only 4-7 pups during its lifetime.

Mobula ray life cycle

Overfishing threatens mobula ray populations

Population declines occur when the rate of loss is higher than the rate at which a population can replenish itself.

Population loss may be the result of natural mortality (e.g., predation or old age) or other factors such as fishing. In Muncar we have recorded juveniles and pregnant females landed in the fishing port. These individuals are lost before they have had a chance to reproduce, compounding the already low productivity of mobula ray populations.

By comparing catch curves to population size-at-age data, Pardo et al. (2016) estimated that fishing mortality was double natural mortality for a mobula population in Mexico. While some fish species can support fishing pressure that is much higher than natural mortality, mobula and similar species with low reproductive rates can not.

Indonesia’s mobula ray fisheries are unregulated

Mobula rays are listed under several multilateral environmental agreements (e.g., CITES Appendix II and CMS Appendix I & II). Indonesia has taken steps to protect similar species such as manta rays and whale sharks. Mobula rays face similar threats and extinction risks, and recent research suggests they may even be in the same genus as manta rays (White et al, 2017). However, mobula rays are not protected or addressed under Indonesia’s national fishery regulations.

Unlike manta rays and whale sharks where target fisheries and wildlife trade are the main threat, a large proportion of mobula landings are unwanted bycatch. This makes it even more challenging for policymakers to develop and implement effective regulations to protect mobula populations.

Fishers have an important role to play

While Indonesia’s national regulations do not yet afford protection to mobula rays, we believe that actions can still be taken to conserve populations and benefit coastal communities.

Our bycatch reduction programme aims to empower fishing communities to play an active role in conserving mobula populations. Working closely with small-scale fishing communities, we are evaluating the feasibility using technologies to reduce unwanted bycatch, and investigating the drivers that incentives fishers to adopt sustainable practices. We are also approaching local communities through our women’s outreach and school outreach programmes to enhance awareness about mobula ray conservation, bycatch mitigation and sustainable seafood markets.

“With Indonesia’s expansive small-scale fisheries, bycatch is arguably the largest threat to mobula populations. Our work aims to equip fishing communities with appropriate knowledge and technologies to maximise the value of their fisheries, whilst minimising unwanted and unsustainable bycatch,”, said Vidlia Rosady, Sustainable Fisheries Coordinator.